Why Africa has to worry about melting Greenland ice

Equi glacier discharging into the sea off Greeenland (Pic. I.Quaile)

Working for an international broadcaster which has Africa as one of its key target groups, I often find it difficult to interest some of my colleagues in what is happening in the Arctic. So my attention was caught instantly when I came across an article by Chelsea Harvey in the Washington Post: A climate chain reaction: Major Greenland melting could devastate crops in Africa.

![]() read more

read more

Climate change is causing rapid, deeper and more extensive acidification in the Arctic Ocean

Scientists measure ocean acidification off the coast of Svalbard. (I.Quaile)

A new study reported in Nature Climate Change this week says ocean acidification is spreading rapidly in the western Arctic Ocean in both area and depth. That means a much wider, deeper area than before is becoming so acidic that many marine organisms of key importance to the food chain will no longer be able to survive there.

The study by an international team including scientists from the USA, China and Sweden, is based on data collected between the 1990s and 2010. Presumably, things have got worse rather than better since then. Unfortunately, it takes a long time for scientific research to be evaluated, reviewed and published, so current developments can easily overtake assessments which are already alarming enough in themselves. So yes, I would say this should make us sit up and listen, and lend even more urgency to the need for reducing emissions and combating climate change.

Acid bath for shellfish

Ocean acidification is a process that happens when carbon dioxide out of the air dissolves in the sea, lowering the pH of the water. This reduces the concentration of aragonite in the water, a form of calcium carbonate which shellfish and other marine organisms use to build their shells or skeletons. If the water becomes too acidic, this cannot be formed to the same extent, leaving the animals without their protective shells.

The latest published research shows that acidification is not only affecting much wider areas of the Arctic Ocean, but also that it is happening down to a much greater depth than before.

Arctic residents like shrimps like cooler water – and need calcium to form their shells. (Pic: I.Quaile, Svalbard, on board Helmer Hanssen research vessel)

Between the 1990s and 2010, acidified waters expanded northward around 300 nautical miles from the Chukchi slope off the coast of northwestern Alaska, to just below the North Pole, the scientists write. At the same time the depth of acidified waters has increased from approximately 325 feet to over 800 feet, or from 100 to 250 metres.

“The Arctic Ocean is the first ocean where we see such a rapid and large-scale increase in acidification, at least twice as fast as that observed in the Pacific or Atlantic oceans”, said Professor Wei-Jun Cai from the University of Delaware and Mary A.S. Lighthipe, Professor of Earth, Ocean and Environment at the same University. Cai is the US lead principal investigator on the project.

“The rapid spread of ocean acidification in the western Arctic has implications for marine life, particularly clams, mussels and tiny sea snails that may have difficulty building or maintaining their shells in increasingly acidified waters”, said Richard Feely, senior scientist with NOAA and a co-author.

Tiny sea snails called pteropods are part of the Arctic food web and important to the diet of salmon and herring. Their decline could affect the larger marine ecosystem.

Among the Arctic species potentially at risk from ocean acidification are subsistence fisheries of shrimp and varieties of salmon and crab.

The polar regions are suffering more than others, because cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

The icy waters of the Arctic are particularly susceptible to acidification (I.Quaile)

Less ice to hold back warm water

The acidification study published this week used water samples taken during cruises by the Chinese ice breaker XueLong (snow dragon) in the summer 2008 and 2010 from the upper ocean of the Arctic’s marginal seas, right up to the North Pole, as well as data from three other cruises going back to 1994. The data, along with model simulations, suggest that increased Pacific Winter Water, driven by circulation patterns and retreating sea ice in the summer season, is primarily responsible for the expansion of ocean acidification, according to Di Qi, the lead author of the paper.

This water from the Pacific comes through the Bering Strait and shelf of the Chukchi Sea into the Arctic basin. Melting sea ice is one factor which allows more of the Pacific water to flow into the Arctic Ocean. The Pacific Ocean water is already high in carbon dioxide and has higher acidity. As it moves north, its acidity increases further for various reasons.

The melting and retreating of Arctic sea ice in the summer months also lets Pacific water move further north than in the past.

The scientists have observed that Arctic ocean ice melt in summer used to occur only in shallow waters with depths of less than 650 feet or 200 meters. But now, it spreads further into the Arctic Ocean.

“It’s like a melting pond floating on the Arctic Ocean. It’s a thin water mass that exchanges carbon dioxide rapidly with the atmosphere above, causing carbon dioxide and acidity to increase in the meltwater on top of the seawater”, said Cai. “When the ice forms in winter, acidified waters below the ice become dense and sink down into the water column, spreading into deeper waters.”

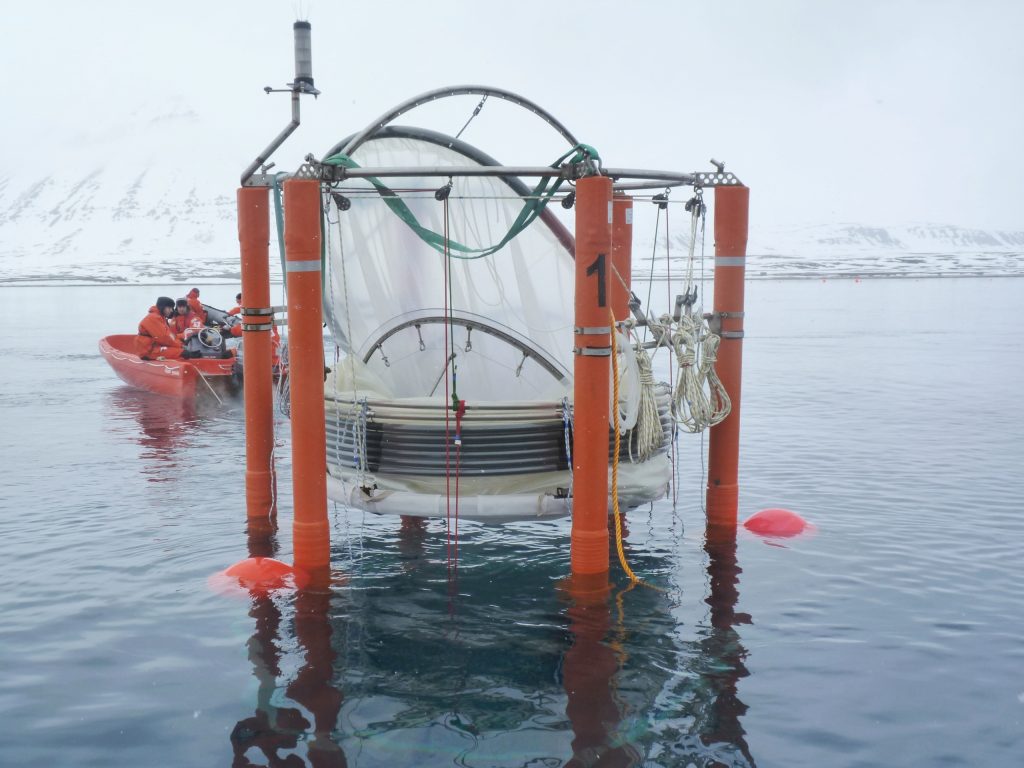

These mesocosms are used to research the effects of acidification on ocean-dwellers. (I.Quaile)

Climate chaos – not just for polar bears

In 2010, I spent some time with scientists conducting the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of Svalbard, to establish exactly how increasing acidification affects the flora and fauna in the Arctic Ocean.

Mesocosms, or giant test-tubes, were lowered into the sea to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades.

Similar experiments are still being conducted in different ocean areas. Results so far have been scary to say the least.

Mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish, coral, fish, “some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future”, Ulf Riebesell from the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, GEOMAR, told me in an interview back in 2013, when he was a lead author of a report by the International Programme on the State of the Oceans (IPSO). He was also one of the scientists in charge of that first Arctic acidification in situ experiment I witnessed back in 2010. He is currently coordinator of the German national project Biological Impacts of Ocean ACIDification (BIOACID).

Riebesell says the sea water in the Arctic could become corrosive within a few decades. “The shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve”, he told me.

Ulf Riebesell supervising the deployment of mesocosms off Svalbard. (Pic. I.Quaile)

Those feedback loops

February 27th was Polar Bear Day. Attention focused on how the decline of sea ice is having devastating impacts on those iconic creatures, who have become a key symbol of the effect of our human-induced climate change on the Arctic. Sea snails may not be quite as charismatic, but the related threat to all these tiny organisms in the water is no less worthy of our attention. Journalist Chelsea Harvey of The Washington Post writes:

“The Arctic is suffering so many consequences related to climate change, it’s hard to know where to begin anymore (…) The study highlights the interconnected nature of climate consequences in the Arctic – the way that greenhouse gas emissions, rising temperatures, ice melt and ocean acidification are all linked and help to reinforce one another. And it points to yet another example of a climate effect that’s not just a concern for the future, but is already an issue – and a growing one – today.”

Indeed, Chelsea. Climate change is already changing our lives and our planet. And, of course, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. The scientists studying ocean acidification and its impacts are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming.

When the IPSO report on the state of the oceans was published, I interviewed the organisation’s scientific director Alex Rogers, a professor of conservation biology at the University of Oxford. He told me the oceans were already taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we are producing. The report said sea water was already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution – and it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate.

“Its buffer capacity will decrease, the more acidic the ocean becomes”, Kiel-based scientist Ulf Riebesell told me.

The IPSO report also drew a very unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions:

“On a lot of these major extinction events we see the fingerprints of high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today”.

Now there is a frightening possibility.

It is not too late to do something about this, although the experts stress the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. The scientists tell us the key step would be to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also to reduce pollution and other pressures on the ocean ecosystem, which reduce its resilience. High time for the Clean Seas initiative, to reduce ocean pollution from marine litter, especially from plastic, launched this week by the United Nations Environment Programme.

Can we halt Arctic melt? Hard question for UN advisor

I had a very interesting high-profile visitor here at Deutsche Welle this week. Bonn, John Le Carré’s “Small Town in Germany” is this country’s UN city nowadays, home to organizations like the climate secretariat UNFCCC and the Convention on Migratory Species, CMS. This year marks 20 years of the former German capital in that new UN role. Fortunately for me and my colleagues, it brings a lot of interesting people to the city.

The University and the City of Bonn have been running a series of lectures by members of the Scientific Advisory Board of the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon this year, under the heading “Global Solutions for Sustainable Development”. This week, it was the turn of Susan Avery, who was President and Director of the Woodshole Oceanographic Institution in the USA until last year. She has been on the advisory board to Ban Ki-Moon for the last three years and she and the other advisors are just finishing their report, so it was great to have the opportunity to talk in length.

Sea and sky as dancing partners

Her lecture was about the importance of the ocean with regard to climate, but she also talked to me about a whole range of ocean-related issues in an interview to be broadcast on our Living Planet programme, starting next week.

Susan Avery is an atmospheric scientist, (the first to head a major oceanographic institution, she told me). She has a very attractive image to describe how the atmosphere and the ocean relate to each other:

“In our planetary system we have two major fluids, the ocean and the atmosphere, and think of them as two dance partners… moving along, but in order to get a choreographic dance, they have to talk to each other. They do that through the ocean-atmosphere interface, which is wave motion, spray, all the things that help them communicate. These two create different dances… an El Nino dance, or a hurricane dance, for example. In reality what they do together is transport heat, carbon and water, which are the major global cycles in our planetary system.”

Since the onset of industrialization, we humans have been introducing some different steps to the dance, it seems:

“When you take it to the climate scale, we talk a lot about the temperature of the atmosphere, increases associated with the infusion of carbon, that is human produced. The thing is that the extra carbon dioxide that gets released into the atmosphere through our fossil fuels and deforestation is associated with extra heat. Of the carbon dioxide we release into the atmosphere, half will stay in the atmosphere, 25% will go into the ocean, 25% will be taken up by the land. But if you look at the heating or warming, 93% of the extra warming is actually in the ocean. There are only very small amounts in the atmosphere.”

Centuries of warming pre-programmed

That means a huge amount of heat is actually being stored in our seas:

“And you can understand why, because the atmosphere is a gas, the ocean is a mass of liquid, which covers two thirds of our planet, and it has a huge heat capacity to store that, but that heat doesn’t just stay at the surface. So (..) when you only talk about heat and temperatures at the surface, you’re ignoring what’s happening below the surface in the ocean, and once the ocean gets heated it’s not going to stay there, because there is this fluid motion. So we’re getting to see greater and greater temperature increases at greater and greater depths. And once that heat gets into the ocean, it can stay there for centuries. Whereas in the upper ocean, it might stay 40 or 50 years, when you get into the deeper parts, because of the density and capacity, it stays there for a long time.”

So, she explained, the carbon dioxide we’ve put into the atmosphere already – and the heating associated with that – means that “we’re already pre-destined for a certain amount of global temperature increase. Many people say we have already pre-destined at least one and a half degree, some will say almost two degrees.”

Now if that is not a sobering thought.

And on top of that comes the acidification of the oceans caused by the extra carbon dioxide, which is playing havoc with coral reef systems and shell-based ocean life forms.

“This is really critical, because it attacks a lot of the base of the food chain for a lot of these eco-systems”.

“What’s in the Arctic is not staying in the Arctic”

Susan Avery’s work has included research on the Arctic and Antarctic, so of course I took the opportunity to ask how she sees all this affecting the polar regions.

She explained how the rapid increase in ice melt in the Arctic – both sea-ice and land ice – caused by atmospheric warming above and warmer ocean waters below, is of great concern for two reasons. The more obvious one is the contribution of land ice melt to sea-level-rise. The other, she explained, is that the melting of the land-based ice results in “a freshening of certain parts of the ocean, so particularly the sub-polar north Atlantic, so you have a potential for interfacing with our normal thermohaline circulation systems which could dramatically change that.” The changes in salinity currently being observed, are a “signal that the water cycle is becoming more vigorous”. This, of course, has major implications for ocean circulation and, in turn, the climate, not just in the region where the ice has been melting:

“What’s in the Arctic is not staying in the Arctic. What’s in the Antarctic is not staying in the Antarctic. I would say the polar regions are regions where we don’t have a lot of time before we see major, massive changes”.

What I find particularly worrying is that Susan Avery confirmed there is still so much we do not know about what is happening in the polar regions and in the ocean in general.

“We really need to get our observations and science and models working together”, she told me. “The new knowledge we have created on processes in the Arctic has to be incorporated into climate system models”.

Satellite data ( KSAT site in in Tromso) helps, but cannot penetrate deep ocean, Avery says. (Pic. I Quaile)

Paris and the poles

So, given that temperature rise of 1,5 to two degrees Celsius could already be a “given”, and the Arctic is being affected much faster and more strongly than the planet on average, is there any real hope that we can hold up these developments and halt the melting of ice in the Arctic? This was clearly a very difficult question for my guest. She told me she had been very relieved that the Paris Climate Agreement was signed and was sure humankind could still “make things better”. But when I asked whether we will really be able to reverse what is happening in the Arctic or halt climate change in the Antarctic, this was what she replied:

“I don’t have an answer, to be honest. I think we’re still learning a lot about the Arctic and its interface with lower latitudes, how that water basically changes circulation systems, and on what scale. But I think what’s really critically needed right now to get a better sense of the evolution of the Arctic, and of sea level rise, is a real concerted observing network. We know so little, about the Arctic, the life forms underneath the ice. We have the technology. What I really see now is a confluence of new technologies, new analytical approaches, new ways to do ocean science, and all it takes is money to really get those robots there, get the genomic studies that you need, the analysis. We are at the stage where we can do so much, to further our understanding, and I would really put a lot into the Arctic right now, if I had the money to do so.”

Me too, Susan.

Ice: the final frontier?

Investigating the undersea secrets of the Arctic night from the research vessel Helmer Hanssen (Pic: I.Quaile)

This brings us back to a key problem I have worried about ever since I started to work on how climate change is affecting the Arctic. That change is speeding up so fast, it is virtually impossible for our research to keep pace. As Susan Avery put it:

“The Arctic will be a major economic zone, we’ve already seen the North-West Passage through the Arctic waters, we’re going to see migration of certain fisheries around the world – and we don’t even know completely what kind of biological life we have below that ice. We have the ability to get underneath the ice now. I call these the frontiers, of the ocean, and that includes looking under ice.”

I am reminded of my trip on board the Helmer Hanssen last year, accompanying a research mission to find out what happens under that ice and down in the deep ocean during the cold, dark season.

(Listen to the audio feature here). There is still so much we do not know about life in the ocean – and it might disappear before we even knew it was there.

Arctic residents in hot water

At the swimming club last weekend, one of my fellow swimmers complained the water was too warm. She said she couldn’t swim at her usual speed when the temperature in the pool rose even a little bit. It left her feeling tired and lethargic. So how much more dramatic must it be for the tiny creatures at home in cold Arctic waters, when a warm influx changes their surroundings and living conditions.?

The warming of Arctic waters with climate change is likely to produce radical changes in the marine habitats of the High North. Data from long-term observations in the Fram Strait, which researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) have now analysed and published in the journal “Ecological Indicators”, confirms that even a short-term influx of warm water into the Arctic Ocean would suffice to fundamentally impact the local symbiotic communities, from the water’s surface down to the deep seas. They found that this happened between 2005 and 2008.

The deep sea observatory

Over the past 15 years, researchers from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for polar and marine science (AWI) have been keeping an eye on the sensitive marine ecosystem in the Fram Strait, the sea lane between Greenland and Svalbard .The institute operates a deep-sea observatory there, known as “HAUSGARTEN”, which translates literally as house garden. It is actually a network of 21 individual mini research stations. Every summer, scientists pay them a visit and collect water and soil samples. Some of the stations have anchored systems that operate year-round, recording the water temperature and tides, collecting water and soil samples at regular intervals, and capturing the sediments that drift down to the seafloor from the upper water layers.

“This is the only observatory of its kind in the world. There’s no other project in which readings from the surface down to the ocean floor were taken in fixed positions over such a long time – let alone in the polar regions,” says AWI biologist Thomas Soltwedel.

For the current publication, the AWI researcher and his team analysed the first 15 years of the HAUSGARTEN dataset. The Fram Strait is especially interesting for Soltwedel and his colleagues because it represents the only deep juncture in the Arctic Ocean, allowing water masses from the Atlantic to flow into the Arctic to the west of Svalbard. In turn, water and ice floes find their way back out of the Arctic Ocean on the strait’s Greenland side.

Too warm for comfort

Until now, the scientists say it was unclear just how polar marine organisms were responding to the warming of the ocean and shrinking sea-ice cover. Now, the long-term observations show that arctic marine habitats could change radically if subjected to a sustained rise in temperature. The AWI researchers say their most surprising finding is that the thermally induced changes at the ocean surface can rapidly spread to affect life in the deep seas.

Normally the water near the surface, which flows north out of the Atlantic through the Fram Strait, has an average temperature of three degrees Celsius. With the help of their observatory, the AWI researchers were able to establish that from 2005 to 2008 the average temperature of the inflowing water was one to two degrees higher: “In that time, large quantities of warmer water poured into the Arctic Ocean. Since polar organisms have adapted to living in constant cold, this extra heat input hit them like a temperature shock,” Soltwedel explains.

He says the reactions in the ecosystem were correspondingly extreme: “We were able to identify serious changes in various symbiotic communities, from microorganisms and algae to zooplankton.”

Migrating sea creatures

One major change described in the article was the increase in free-swimming conchs and amphipods, which are normally found in the more temperate and subpolar regions of the Atlantic. In contrast, the number of conchs and amphipods in the Arctic dropped significantly.

The researchers also noted a decline in small, hard-shelled diatoms. Prior to the unexpected influx of warm water, they made up roughly 70 per cent of the vegetable plankton in the Fram Strait. But during the warm phase, the foam algae Phaeocystis took their place. A change with consequences, Soltweder explains: “Unlike diatoms, foam algae tend to clump and sink to the ocean floor, where they become a food source. But the sudden rise in available food led to major changes in deep-sea life, including a noticeable increase in the settlement density of benthic organisms.”

If you are not a marine biologist, you may be wondering what that means for the future of the Arctic and why we should be concerned about it. The problem is that all of this affects the Arctic food web.

The scientists can’t say exactly how at this point. But, as with so many other aspects of climate change: “Above all, we’re troubled by the simple fact that the changes have been so rapid, and so far-reaching.”

New residents here to stay

Since the flow of warm water has subsided, the water temperature in the Fram Strait has stabilised – though it is still slightly above the average value from before 2005. Yet some of the changes appear to be there to stay. The conchs from the lower latitudes seem to have made a home for themselves in the Fram Strait.

As usual, the scientists are reluctant to say whether the warm-water influx they monitored is due to climate change or could be part of natural climate fluctuations. They say they need data covering several decades to be more certain.

But either way, the results of the ecological long-term studies clearly show that even short-term changes in ocean temperature can drastically impact life in the Arctic. So it looks like there will certainly be more to come, as the world continues to heat up.

Polar ice set for six-metre sea level rise?

Small increases in global average temperature may eventually lead to sea level rise of six metres or more, according to evidence from past warm periods in Earth’s history.

That was the worrying message from a paper published in the journal Science this week. The researchers, part of the international “Past Global Changes” project, analysed sea levels during several warm periods in Earth’s recent history, when global average temperatures were similar to today or slightly warmer – around 1°C above pre-industrial temperatures.

I was able to talk briefly to one of the authors, Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), who was in Paris at the international scientific conference “Our common future under climate change” this week. (The article I wrote on that event, billed as the biggest climate science gathering ahead of the key COP in Paris in December, and the full interview with Rahmstorf are online now).

Rahmstorf described the new study on polar ice sheet disintegration and sea level as “a review of our state of knowledge about past changes in sea level in earth’s history, especially looking at all the data we have on past warm periods, due to the natural cycles of climate – the ice age cycles – that come from the earth’s orbit.”

He went on: ”We have had warmer times in the past, the last one was about 120,000 years ago, and we find that invariably, during these warmer times, the sea level was much higher. It was at least about six meters higher than today, even though temperatures were only a little bit higher, maybe one to three degrees warmer – depending on what period you are looking at – compared to the pre-industrial climate.”

Bad news for coastal dwellers

Not happy reading for anyone living close to the coast, if you look at temperature development today:

“Basically the message is: the kind of climate we are moving towards now – even if we limit warming to two degrees – has in the past always been associated with a sea level several metres higher, which would of course have catastrophic consequences for many coastal cities and small island nations.”

With warming currently on course to reach four degrees and more by the end of this century if greenhouse gas emissions continue on their present trajectory, this message adds yet another piece of evidence to motivate the world’s governments to come up with a new World Climate Agreement at the UN Paris summit at the end of the year – and to get moving towards a zero-carbon economy asap.

The interdisciplinary team of scientists concluded that during the last interglacial warm period between ice ages 125,000 years ago, the global average temperature was similar to the present, and this was linked to a sea-level rise of 6 to 9 metres, caused by melting ice in Greenland and Antarctica. Around 400,000 years ago, when global average temperatures were estimated to be between 1 to 2 degrees Celsius higher than –pre-industrial levels, sea level reached 6 to 13 meters higher. The lead author of the study, Andrea Dutton from the University of Florida, told journalists global average temperatures were similar to today during these recent interglacial periods, but polar temperatures were slightly higher. However, she stressed: “The poles are on course to experience similar temperatures in the coming decades”.

The Arctic is currently warming faster than the global average. IPCC estimates indicate that it could be almost two degrees warmer by 2100 compared with the temperature from 1986 to 2005 – IF the two-degree target is adhered to. Otherwise, it could rise by as much as 7.5°C.

Speed of sea level rise hard to predict

The authors of the study stress that the further back you go (they tried to estimate sea level as long as three million years ago), the more difficult it gets to calculate precisely how high sea level was, given that geological forces push and pull the Earth’s surface and can also cause vertical movement measuring tens of metres. This makes it hard to separate the geological changes in shoreline position from sea level rise caused by polar ice sheet disintegration.

Still, the authors point out that small temperature rises of between one and three degrees were, in the past, like today, linked with magnified temperature increases in the polar regions, which lasted over many thousands of years.

They conclude that even keeping to the overall two-degree warming limit is no guarantee: “Even this level sustained over a long period of time carries substantial risk of unmanageable sea level rise, not least because carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for over a thousand years”.

The researchers are not able to say how fast sea levels rose in the past, which would be a key piece of information for planning adaptation. Further research will be necessary for that.

Co-author Anders Carlson of Oregon State University says by confirming that our present climate is warming to a level associated with significant polar ice-sheet loss in the past, the study us providing “perhaps the most societally relevant information the paleo record can provide”.

Carlson heads the PALSEA2 Working Group, hosted by the Past Global Changes (PAGES) project, which used computer models and evidence from around the globe to come up with the conclusions in the study.

Stefan Rahmstorf draws a clear conclusion from the results of this research and other recent studies on instabilities in the Antarctic ice sheet and changes in ocean currents:

“This really calls for limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. And it is still feasible to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. But that requires a much stronger political will than we currently have”.

Still, the Potsdam professor is more optimistic than he used to be that advances in renewable energy and other technologies and growing awareness of the negative impacts climate change is already having around the globe could mean the UN Paris conference at the end of the year will mark a turning point.

Not that he thinks Paris can “do it all”. As you’ll see if you read my interview with him, he is hoping for the start of a process similar to the Montreal Protocol, where the original agreement was not too strong, but worked eventually by toughening up as it went along. Now that would be really good news. He told me it was time to “turn the tide of rising emissions”. Here’s hoping it happens in time to keep the sea level around the world well below that six metres that were there in the past.

Feedback